Dead weight loss is a key concept in economics that measures the lost efficiency in a market. Whenever a market is distorted by taxes, subsidies, price controls, or monopolies, the total welfare of society decreases.

This means that some potential gains for both consumers and producers are not realized, creating a “loss” that affects the overall economy. Understanding deadweight loss is important not just for economists, but also for policymakers, business leaders, and anyone interested in how markets function.

For example, when a government imposes a high tax on a product, it may reduce the quantity bought and sold, causing a dead weight loss. Similarly, monopolies can charge higher prices and limit supply, leading to economic inefficiency.

In this article, we will explore the definition of dead weight loss, its causes, real-life examples, methods of calculation, and ways to reduce its impact on markets.

What is Dead Weight Loss?

Dead weight loss (DWL) is an economic concept that represents the loss of total welfare in a market due to inefficiencies. In simple terms, it occurs when resources are not allocated in the most efficient way, resulting in lost opportunities for both consumers and producers. DWL is commonly caused by taxes, subsidies, price controls, and monopolies, all of which prevent a market from reaching its optimal equilibrium.

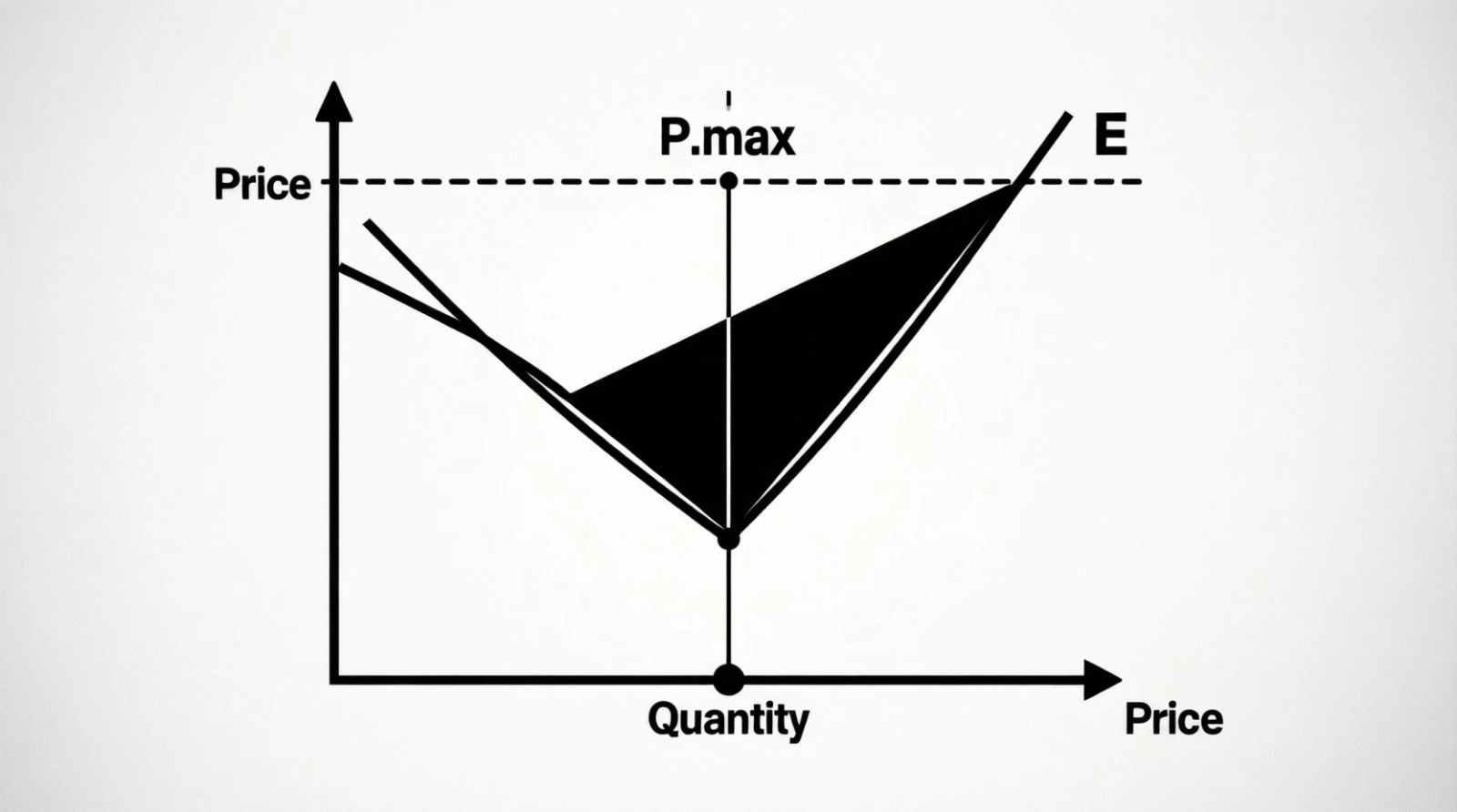

To understand this better, imagine a simple market for a product. Without any interference, the supply and demand curves intersect at the equilibrium price and quantity, maximizing total welfare. Both consumers and producers benefit: consumers pay a fair price, and producers receive fair revenue. Now, suppose the government imposes a tax on the product. The price rises for consumers, and the quantity sold decreases. Some buyers who would have purchased the product at the original price no longer do, and some producers who would have sold at the original price reduce their output. The result is a triangle-shaped area on the supply-demand graph that represents lost economic value—this is the dead weight loss.

Dead weight loss is important because it highlights the inefficiency that can occur in markets. While taxes and regulations may be necessary for other purposes, understanding DWL helps policymakers minimize economic waste. By analyzing consumer and producer surplus, economists can measure exactly how much value is lost and explore ways to reduce it.

Causes of Dead Weight Loss

Dead weight loss occurs whenever a market is prevented from reaching its most efficient outcome. There are several common causes that create this economic inefficiency. One major cause is taxes and tariffs. When governments impose taxes on goods or services, the price for consumers increases, and producers receive less revenue. This reduces the quantity bought and sold, leading to lost opportunities for both parties. For example, a high tax on cigarettes may discourage some buyers, which lowers total market welfare.

Another significant cause is price controls, such as price ceilings and price floors. A price ceiling, like rent control, keeps prices artificially low, resulting in shortages. Producers may not supply enough, and some consumers may miss out on housing, creating dead weight loss. Conversely, price floors, like minimum wage laws or agricultural price supports, keep prices higher than the market equilibrium, leading to surpluses and wasted resources.

Monopolies and lack of competition also create dead weight loss. A monopolist restricts output to increase prices, which reduces the quantity sold and prevents some mutually beneficial trades from happening.

Finally, externalities—both negative and positive—can cause DWL. For instance, pollution creates costs for society not reflected in the market price, while subsidies for overproduced goods can distort markets.

Understanding these causes is crucial because it helps policymakers design interventions that minimize inefficiency while still achieving social or economic goals. By identifying the source of dead weight loss, strategies can be applied to reduce its impact on the economy.

How to Calculate Dead Weight Loss

Calculating dead weight loss is essential to measure the efficiency lost in a market. Economists typically use a simple formula to estimate DWL:DWL=12×Quantity Reduction×Price Change\text{DWL} = \frac{1}{2} \times \text{Quantity Reduction} \times \text{Price Change}DWL=21×Quantity Reduction×Price Change

This formula works because dead weight loss is represented as a triangle on the supply and demand graph. The base of the triangle is the reduction in quantity due to a market distortion, and the height is the change in price caused by the distortion, such as a tax or price control.

For example, imagine a market where 1,000 units of a product are sold at $10 each. If a tax causes the quantity sold to drop to 800 units and the price rises to $12, the DWL can be calculated as:DWL=12×(1,000−800)×(12−10)=12×200×2=200\text{DWL} = \frac{1}{2} \times (1,000 – 800) \times (12 – 10) = \frac{1}{2} \times 200 \times 2 = 200DWL=21×(1,000−800)×(12−10)=21×200×2=200

So, the market loses $200 in total welfare due to the tax.

Graphically, DWL is the area between the supply and demand curves that disappears because the market no longer reaches equilibrium. The triangle shows the trades that could have happened but didn’t due to the distortion.

Understanding this calculation helps policymakers evaluate the economic impact of taxes, subsidies, or price controls. By measuring DWL, they can design policies that minimize market inefficiencies while achieving social goals.

Real-Life Examples of Dead Weight Loss

Dead weight loss is not just a theoretical concept; it occurs in many real-world markets. One common example is taxation. Governments often impose taxes on goods like cigarettes, alcohol, or sugary drinks to generate revenue and discourage consumption. While taxes achieve these goals, they also reduce the quantity bought and sold. Some consumers stop buying the product because of higher prices, and some producers sell less, creating lost transactions that represent dead weight loss.

Another example is price controls. Rent control in housing markets is a well-known case. By setting maximum rents below equilibrium, landlords may supply fewer apartments, and some renters cannot find housing. The resulting shortage represents a dead weight loss because both potential renters and landlords miss out on mutually beneficial exchanges. On the other hand, price floors, like minimum wage laws or agricultural subsidies, can lead to surpluses. For instance, paying farmers above-market prices for crops may result in overproduction, with excess goods wasted, creating inefficiency in the market.

Monopolies also cause dead weight loss. A company with exclusive control over a product may charge higher prices and limit output to increase profits. Consumers who would have purchased the product at a fair price are left out, while the producer does not sell as much as in a competitive market.

Even subsidies intended to help certain industries can create DWL if they encourage overproduction or misallocation of resources. Understanding these real-life examples helps policymakers and businesses recognize inefficiencies and make better economic decisions.

Effects of Dead Weight Loss on the Economy

Dead weight loss can have significant consequences for both consumers and producers, affecting the overall health of an economy. At its core, DWL represents lost potential gains—transactions that could have benefited both parties but did not occur because of market inefficiencies. This loss reduces total welfare, meaning society as a whole is worse off.

For consumers, dead weight loss can lead to higher prices, reduced availability of goods, or lower quality products. For example, a tax on gasoline may raise prices, forcing some drivers to cut back on purchases or commute less. Similarly, monopolies can charge higher prices and produce less, leaving some consumers unable to access the product at all.

For producers, DWL can mean lost revenue and underutilized resources. In markets with price controls or monopolies, producers may either produce less than optimal or fail to sell to potential buyers. Over time, this misallocation of resources can lower profits and discourage investment.

At the macroeconomic level, widespread dead weight loss can slow economic growth. Markets fail to allocate resources efficiently, reducing the total output of goods and services. Governments may also collect less effective revenue when DWL occurs from poorly designed taxes or subsidies.

In short, dead weight loss decreases efficiency, misallocates resources, and reduces total welfare in the economy. Understanding these effects is crucial for policymakers, economists, and business leaders who aim to create efficient, fair, and productive markets.

Ways to Reduce Dead Weight Loss

While dead weight loss is common in many markets, there are strategies that policymakers and businesses can use to minimize it. One of the most effective ways is designing efficient tax policies. For example, lump-sum taxes, which are fixed amounts unrelated to quantity bought or sold, create minimal distortion in the market. Lowering excessively high taxes on goods can also reduce dead weight loss by encouraging more transactions to occur.

Encouraging competition is another important strategy. Markets dominated by monopolies or oligopolies often produce less and charge higher prices, creating DWL. By supporting smaller businesses, removing barriers to entry, and preventing anti-competitive practices, governments can help markets reach more efficient outcomes.

Smart subsidies can also reduce DWL when carefully targeted. Instead of over-subsidizing industries, governments should focus on areas where social benefits exceed market costs, such as education or research. Poorly targeted subsidies can distort production and lead to inefficiency, so careful planning is crucial.

Reducing price controls where possible also helps. For example, gradually adjusting minimum wages or rent controls to reflect market conditions can reduce shortages or surpluses. Flexible pricing allows supply and demand to balance naturally, minimizing lost welfare.

Finally, correcting negative externalities in a market-friendly way can reduce dead weight loss. For instance, pollution taxes or tradable carbon credits internalize costs without overly restricting trade.

FAQs

1. What is the difference between dead weight loss and lost revenue?

Dead weight loss refers to the economic value lost due to market inefficiency, where potential trades do not happen. Lost revenue, on the other hand, is the money a business or government does not earn, which may or may not correspond to efficiency loss. DWL focuses on total welfare, not just money collected.

2. Can dead weight loss be completely eliminated?

In theory, a perfectly competitive market with no taxes, subsidies, or externalities would have zero dead weight loss. In practice, some DWL is unavoidable because governments need taxes to fund services, and markets cannot always be perfectly competitive. However, careful policies can minimize it.

3. How do economists measure dead weight loss?

Economists calculate DWL using supply and demand curves. By analyzing changes in price and quantity caused by taxes, subsidies, or other distortions, they measure the triangle-shaped area representing lost welfare. Numerical formulas can also estimate the size of DWL.

4. What are some common examples of dead weight loss?

Examples include taxes on goods like cigarettes, monopolistic pricing, rent-controlled housing shortages, and over-subsidized industries. All these distort market equilibrium and reduce total welfare.

5. Why is understanding DWL important?

Understanding dead weight loss helps policymakers design efficient taxes, subsidies, and regulations, and allows businesses to assess market inefficiencies. By minimizing DWL, economies can improve resource allocation and maximize overall welfare.

Conclusion

Dead weight loss is a crucial concept in economics that highlights the cost of market inefficiencies. It occurs whenever resources are not allocated in the most efficient way, resulting in lost opportunities for consumers, producers, and society as a whole.

Common causes include taxes, subsidies, price controls, monopolies, and negative or positive externalities. Each of these market distortions prevents the equilibrium price and quantity from being reached, creating lost welfare that can be measured both graphically and numerically.

Understanding dead weight loss is not just an academic exercise it has real-world implications. For consumers, it can mean higher prices or reduced access to goods and services.

For producers, it can lead to lost revenue and underutilized resources. At a broader economic level, widespread DWL can slow growth, misallocate resources, and reduce overall societal welfare.

Fortunately, there are ways to minimize dead weight loss. Efficient tax policies, encouraging competition, carefully targeted subsidies, flexible pricing, and correcting negative externalities can all help reduce inefficiencies.

By applying these strategies, governments, businesses, and policymakers can improve market outcomes and ensure resources are better allocated.

In conclusion, dead weight loss serves as a warning about the consequences of economic distortions. By understanding its causes, measuring its impact, and implementing strategies to reduce it, we can create more efficient markets that maximize total welfare.

Awareness of DWL allows both individuals and policymakers to make smarter decisions that benefit the economy and society as a whole.

I’m Robert Silva, a quotes expert at Quotesfuel.com — delivering powerful words and daily inspiration to keep your spirit fueled!